Our Curriculum

In each of the Primary classes we will meet about 25-30 children working with two adults. In these schools, both adults in each class are trained in the Montessori approach and work together as a team. Some schools prefer to staff their classes with one certified teacher and one or more assistants. To become a Montessori "Guide" or "Directress" as they are called in some schools, the teachers went through a demanding course of graduate level study. Each classroom is fairly spacious compared to what we usually find in traditional nursery schools. It is clear that someone took great pains in designing the space, selecting the furnishings and creating an atmosphere of simple beauty. Several things stand out as being different from the typical classroom for young children. There are no blackboards

at the front of the room. There are no posters of cartoon-like animals, no cardboard alphabet hung on the walls, or the familiar collection of dozens of identical art projects.

Instead the classroom is divided into several logical areas by low open shelves, on which we see displayed an array of lovely and intriguing learning activities. We may not know what they are called, what they do or why they are used, but they draw our attention and make most adults visiting a Montessori class long to be a child once again. Although it may not be immediately obvious, there is an order to the room and a careful structure of how things are arranged. The teachers will tell you that their environment is divided up into several areas: one for Practical Life, one for Sensorial, one for Language, another one for Math and probably somewhat smaller areas for Art, Music, Geography and Science. History at the Primary level includes a fascinating series of exercises and activities to introduce a young child to the concepts of time and the early stories of how the Earth was created and how life and eventually people evolved on it. The exercises on each shelf are arranged in a highly logical order. They are placed in the room according to their logical category such as Practical Life or Mathematics; any logical sub-grouping, such as pouring or fraction work; from the most simple idea to the most complex; and from the most concrete way of representing each concept to the most abstract. According to this scheme, materials are displayed on the shelves from the top-left corner to the right side, down a shelf and moving again from left to right, until we come to the lower-right corner. Each material isolates one concept or skill. Each has been designed so well that it "calls to the child", or more clearly said, it is so beautifully designed, that the children naturally want to work with it with little or no nudging from adults. Each material has also been designed so that a child can check his own work; we call this a built in "control of error".

Basic Structure of the curriculum

Dr. Montessori's research let her to conclude, that intelligence is not rare among human beings. It manifests itself in the natural, spontaneous curiosity of the young child from birth. Montessori observed that when children grow up in an environment that is intellectually and artistically alive, warm and encouraging, they will spontaneously ask questions, investigate, create and explore new ideas. She found that children, especially when they are young, are capable of absorbing information, concepts, and skills from their surroundings and peers almost through osmosis. Dr. Montessori argued that learning can and should be relaxed, comfortable natural process. The secret is to pay attention to the hidden nature of the child at a given stage of development and to design an environment at home and school in which they will begin to fulfill their innate human potential. Montessori as an educational approach is not designed simply to teach children basic skills and information. In addition to becoming culturally literate, children need to learn to trust their own ability to think and solve problems independently. Montessori encourages students to their own research, analyze what they have found and come to their own conclusions. The goal is to lead students to think for themselves and become actively engaged in the learning process. Rather than give the students the right answers, Montessori teachers tend to ask the right questions and lead students to discover the answers for themselves. Learning becomes its own reward and each success fuels a desire to discover even more. Dr. Montessori found that at every age level, students learn in different ways at different rates. Many learn much more effectively form direct hands-on experience than from studying a textbook or listening to a teacher's explanations. But all students respond to careful coaching with plenty of time to practice and apply new skills and knowledge. Like the rest of us, children tend to learn through trial, error and discovery. Montessori students learn not to be afraid of making mistakes. They quickly find that few things in life come easily and they can try again without fear of embarrassment.

Yearly Cultural Curriculum

Astronomy

The Universe. The Solar System

Geography

The Earth, Study of the Globe, Continents, Land and Water Formations, Oceans and Zones.

Racial Groups

Native American, Caucasoid, Negroid, Mongoloid, Composite Group, Myself, My Family, Children around the World, People around the World

Role Models

Famous Personalities from around the World

Music Composers

Famous Composers and Music from around the World

Human Values

Truth, Right Action, Peace, Love, Non-Violence, Compassion, Self-esteem, Kindness, Respect, Human Differences and Similarities

History

Early Life on Earth (Animal and Plant), The Needs of Man, Days of the Week, Months of the Year, Seasons of the Year, Calendar, Early Civilizations, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Modern Ages

Human Anatomy

Health and Physical Hygiene, The Food Pyramid, Cleanliness and its importance, Exercise, Parts of the Body, Senses of the Body, Internal Organs, Emotions

Biology

Living - Non Living, Animal - Plant

Botany

Fruits and Vegetables, The Plant, The Leaf, The Flower, The Root, The Seed, The Stem

Zoology

Vertebrate - Invertebrate, The Five Groups of the Vertebrate, The Fish, The Amphibian, The Reptile, The Bird, The Mammal, The Insects

Science

Observation Table, Magnifying Glass, Sink and Float, Magnetic - Non Magnetic, Three Forms of Matter: Land - Air - Water, Animal - Plant - Mineral, Weather, Clouds, The Clock

Community

My Community, The Farmer, The Policeman, The Dentist, The Fireman, TheVeterinarian, The Librarian, The Postman, The Doctor, The Nurse, The Banker

The Montessori Curriculum Integrates Knowledge

The Montessori curriculum is organized as an inclined spiral plane of integrated studies rather than traditional model in which the curriculum is compartmentalized into separate subjects with topics considered only once at a grade level. Lessons are introduced simply and concretely in the early years and are reintroduced several times over the following years at increasing degrees of abstraction and complexity. The Montessori course of study is an integrated thematic approach that ties the separate disciplines of the physical universe, the world of nature and the human experience. Literature, the arts, history, social issues, civics, economics, science and the sturdy of technology all complement each other in the Montessori curriculum. This integrated approach is one of Montessori's great strengths. As an example, when Elementary Montessori students study Africa, they look at the physical geography, the climate, ecology, natural resources and the ways in which people have adapted to their environment: food, shelter, transportation, clothing, family life and traditional cultures. The might read African folk tales, study great African civilizations and endangered species, create African masks and traditional instruments and make African block print T-shirts in art, learn some Swahili, study dance and music and prepare some typical meals from various African cultures. Guest speakers, performers and friends of the school help to make the curriculum come alive through their memories, talents and personal experience.

The Practical Life

The intention of the materials is not to keep the children dependent on these artificial learning aids forever, but to use them as a tool to help children be able to work and learn at their own pace, to see abstract ideas presented in a very concrete three-dimensional way and to help them to understand.

The children normally come to school for five days a week. Most Montessori schools do not offer two- or three-day programs, because young children are incredibly responsive to consistency and order in their environment.

When a child comes to school only a few days a week, he never attains that consistency and order. In some schools, two three and four year olds go home at noon, while in many others they stay for the full day.

Success in school is directly tied to the degree to which children believe that they are capable and independent human beings. If they knew the words, even very young children would ask: Help me learn to do it for myself. As we allow students to develop a meaningful degree of independence and self-discipline, we also set a pattern for a lifetime of good work habits and a sense of responsibility. In Montessori, students are taught to take pride in their work. Independence does not come automatically as we grow older; it must be learned. In Montessori even very small children can learn how to tie their own shoes and pour their own milk. At first shoelaces turn into knots and milk ends up on the floor. However, with practice, skills are mastered and the young child beams with pride. To experience this kind of success at such an early age builds a self-image as a successful person and leads the child to approach the next task with confidence. Working with nature, both in and out of the classroom helps Montessori students integrate conceptual science with practical-life skills. Students of all ages experience the excitement of watching their seedlings develop into beautiful flowers for a floral arrangement to decorate their classroom with edible vegetables to prepare for a midmorning snack. In a very real sense, Montessori children are responsible for the care of this child size environment, which is why Dr. Montessori called it a "Children's House" or "Community".

They sweep, dust and wash mirrors and windows. They set tables, polish silver and steadily grow in their self-confidence and independence. The lessons in practical-life skills do much more than help children learn to wash tables. The process helps them develop an inner sense of order, a greater sense of independence and a higher ability to concentrate and follow a complex sequence of steps. As they get older, Montessori students learn all sorts of everyday living skills, such as using computers, household cleaning, cooking, sewing, first aid and balancing a checkbook. They plan parties, learn how to decorate a room, arrange flowers, garden and do simple household repairs. Montessori builds many opportunities into the curriculum for students to gain hands-on experience.

Learning how to work and play together with others in a peaceful and caring community is perhaps the most critical life skill that Montessori teaches. Montessori schools are intended to be close knit communities of people living and learning together in an atmosphere of warmth, safety, kindness and mutual respect. Teachers become mentors and friends. Students learn to value the different backgrounds and interests of their classmates.

The Sensorial Exercises

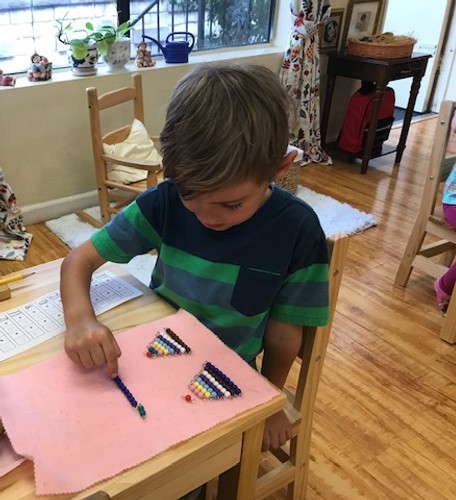

A child interacts with the physical world through his senses. From birth, he will look, listen, touch, taste, pick up, manipulate and smell almost anything that comes into her grasp. At first, everything goes into the mouth. Gradually he begins to explore each object's weight, texture, and temperature. He may watch something that catches his attention, such as a butterfly, with infinite patience. The Sensorial curriculum is designed to help the child focus his attention more carefully on the physical world, exploring with each of his senses the subtle variations in the properties of objects.

At first, the child may simply be asked to sort among a prepared series of objects that vary by only one aspect, such as height, length or width. Others challenge him to find identical pairs or focus on very different physical properties, such as aroma, taste, weight, shades of color, temperature or sound. These exercises are essentially puzzles and they tend to fascinate the children because they are just difficult enough to represent a meaningful challenge. Each has a built-in control of error that allows the child who is observant to check his own work. All the Sensorial exercises are essentially lessons in vocabulary, as the children master the names of everything from sophisticated plane and geometric figures to the parts of familiar plants and animals. As the Eskimos demonstrate to us with 26 different words the snow, we observe that as the children learn the correct names for things, the objects themselves take on meaning and reality as the child learns to recognize and name them.

Why is it so important to educate the young child's senses? We certainly don't believe that we can improve a child's hearing or sight through training. However, we can help children pay attention, to focus their awareness and to learn how to observe and consider what comes into their experience. In a way, the Sensorial curriculum accomplishes something like a course in wine tasting or music appreciation; one learns to taste, smell or hear what is experienced with a much deeper awareness and appreciation. These exercises can help the children learn and appreciate their world more fully.

The Pink Tower is one of the Sensorial materials that children enjoy working with early in their Montessori experience. The Pink Tower is composed of a graduated series of 10 wooden cubes.

The largest cube has a square section of 10 centimeters per side and is 10 centimeters high.

Thus, it measures 10 x 10 x 10 centimeters. The square section and height of the succeeding cubes decreases by one centimeter down to the smallest cube which measures 1 x 1 x 1 centimeter.

Children carefully carry the tower, cube by cube, to the little rug that defines their work area.

They carry each cube comfortably at waist height as they take the cubes and place them in random order upon a rug. As they manipulate the cubes and carry them across the room, the children get a very strong impression of size and weight.

When all the cubes have been carried to the rug, the child looks for the largest one and begins to build the tower, one cube at a time.

At each step, the child looks through the cubes that have not yet been added to the Tower to find the largest. As each is placed on the tower, the child controls his movements to place the cube gently down right in the center of the larger cube on which is rested.

Once the tower has been constructed, the child carefully takes it down and either begins again or returns the cubes, one by one, to their little shelf.

All of the Sensorial materials also lead into vocabulary lessons and language. For example the child working with the Pink Tower masters the terms smaller, smallest, larger and largest.

The Brown Stairs, which is sometimes called the Broad Stairs, is made up of 10 rectangular prisms with bases that have exactly the same graduated measurements as the cubes of the Pink Tower, but which are uniformly 20 centimeters long. The child is challenged to scatter them on the rug and sort them by size to place all 10 prisms in proper order from thickest to thinnest. This results in a graduated series of rectangular prisms that resembles a little stairway. Because the squared sides of each prism correspond to the dimensions of the cubes of the Pink Tower, the two materials are sometimes used together for all sorts of explorations and designs.

Some people have heard, that in Montessori the children are taught there is only one way to work with each material. In truth, the children explore and discover all sorts of creative work with them. For example, they will construct the Tower horizontally or line up two edges to create a vertical stairway. The children will also build the Pink Tower in various combinations with the Brown Stairs along with some of the other Sensorial materials.

The Red Rods are a series of 10 rods (thin rectangular prisms) in which the height and width are uniform, but which range in length from one decimeter (10 centimeters) to a full meter (10 decimeters or 100 centimeters). The child scatters them on the rug and looks for the longest. As each in turn is arranged along side of the other in a series, they help the child discover the regular progression of length. The teachers introduce vocabulary: short, shortest, long, longer, longest. The Red Rods are quite similar to the Red and Blue Rods in the Math area, which help the child learn to count by showing the growth of quantity as length, distinguished by alternating patterns of red and blue to represent each decimeter.

The Cylinder Blocks are a set of four naturally finished (unpainted) rectangular blocks of wood, into which have been cut 10 cylindrical holes. Each hole is filled with a matching wooden inset fitted with a little knob on the top to make it easy for a child's small hand to grasp and lift the inset out of its perfectly fitted hole.

Each set of cylinders is constructed to vary in a regular sequence by either diameter, depth or both. The children remove each cylinder in turn, carefully placing it in order on the table. Once all 10 cylinders have been removed and placed on the table, the children take each in turn and find the hole into which it fits perfectly with the tip of the cylinder flush with the top of the cylinder block. If they've made a mistake, the children can normally see it for themselves because all 10 cylinders will not fit correctly.

The children quickly begin to challenge themselves by attempting to "see" which hole is likely to fit the cylinder in their hand rather than trying to fit each into one hole after the other. After a while, they will begin to do the same exercise with their eyes blindfolded, relying on touch alone. When they are ready for a great challenge, the children will mix the cylinders from two, three or all four blocks together and try to fit them into the corresponding holes.

The Knobless Cylinders correspond to the four Cylinder Blocks. In this material, the set of each cylinder is painted red, yellow, blue or green. With no cylindrical holes, the children depend upon width or touch alone to arrange the cylinders. They will often work with both, the Knobless Cylinders and the more familiar Knobbed Cylinders from the Cylinder Blocks together, finding the match between each brightly painted and unpainted cylinder in turn. By working all four sets of Knobless Cylinders together, the children discover all sorts of geometric patterns and progressions within the material.

The Color Tablets help the child learn to distinguish among primary and secondary colors and tones, while mastering the words used to describe each color and shade. There are three separate boxes of Color Tablets. All of the tablets have the same shape and differ only in color. The first box of Color Tablets contains six tablets, two each of yellow, red and blue. The children simply match the pairs and learn the spoken names of the colors. The second box of Color Tablets contains eleven pairs of secondary colors and tones, which the children match and name.

The third box of Color Tablets contains seven different shades of nine different colors, which the children learn to sort in order from the darkest to the lightest shade. When all the tablets are laid out, they created a lovely display of color. There are many ways in which the children and teacher can make the Color Tablets more challenging. For example, children can try to find the tablet that is closest in color to something in the environment. Another challenge is to give the child a Color Tablet from the third box and ask him to go to the box and, by memory alone

bring back the tablet that is just one shade lighter or darker.

Touch - the children commonly put on blindfolds to add an additional level of challenge as they sort or construct with the Sensorial materials. They love to explore their sense of touch. One of the children's favorite activities is the Mystery Bag.

Normally it is simply a cloth bag or box with a hole for their hands in which they touch and manipulate objects that they cannot see. One activity is to place things that are familiar to the children inside, and challenge them to identify them by touch alone.

Another exercise begins with the Rough and Smooth Boards, which have a surface that alternates between the roughness of sandpaper and a smooth finished surface. The children wash their hands in warm water before beginning to make them more sensitive.

The Sandpaper Tablets are a set of wooden tablets covered with several different grades of sandpaper. The challenge is to identify pairs that have the same degree of roughness, working by touch alone. An extension of these activities is commonly created by assembling a collection or pairs of cloth swatches cut from many different materials, each with its own texture. Again, working with eyes blindfolded, the children attempt to find the pairs by touch. Like all Montessori exercises, there is a built-in control of error. In this case the children can check their work by removing the blindfold and seeing if the pairs look the same.

The Thermic Tablets - the thermic sense is the ability to distinguish among objects with different temperatures. The Thermic Tablets are a series of pairs of objects of identical size that are made from different material such as wood, stone and metal. The material tends to feel quite differently from each other at room temperature when lightly touched by a blindfolded child. The challenge is to match them by temperature. The language of temperature is also taught: hot, cold, hotter, hottest, warm, warmer, warmest, cool, cooler, coolest etc.

The Baric Tablets - the baric sense is the ability to distinguish among different objects by weight. The Baric Tablets come as a box containing three sets of little wooden tablets, identical in size, but made out of three different woods. One wood is very light; the next is made of a heavier material and the third quite heavy for its size. The child puts on a blindfold and sorts among the scattered tablets to find identical pairs or to determine which in any given set of two is lighter or heavier.

The Smelling Bottles resemble small spice containers with lids that have small holes through which the material inside can be smelled but not seen. The teacher prepares a set of six pairs. One set of six typically has red caps, the other has blue. The child is challenged to find the identical pairs. Gradually the child learns to identify the source of the aroma. These exercises are extended beyond the classroom to the kitchen, garden and nature walks. The children are blindfolded and asked to identify flowers, spices and so on by their aromas. The materials inside the smelling jars are varied every few weeks to give the child an ever-changing challenge.

The Sound Boxes are designed to begin the process of teaching the child to listen attentively. It consists of a set of twelve hollow wooden cylinders, six of each has red caps and six of which has blue. Each set of six appears identical except for the color of its cap. Inside each set, six different substances (such as sand, dry rice or dried peas) create distinct sounds when the cylinder is shaken. The child arranges the cylinders into two sets according to the color of their caps and attempts to match the identical pairs by sound alone. Once the children can accomplish this, they learn to grade them from the softest to loudest sound.

The Montessori Bells extend the child's ability to distinguish sounds into each area of musical pitch. They are a lovely set of bells fixed to a wooden base. Each bell is tuned to either a whole or a half note on the standard musical scale. The entire set comprises one entire octave, including sharps and flats. The set includes one set of bells with tan bases for both half and whole notes and a second set in which the bases of the bells that sound the whole notes are painted white and those for the sharps and flats are painted black. At first children learn how to strike the bells with a small mallet to produce a clear note and damp them with a little felt covered rod. Then the teacher sets out two or three pairs of bells from the tow sets. The children match the pairs that produce identical notes. When they can do this easily, additional pairs are added until they can match the entire sets. A more difficult exercise challenges the children to grade the bells of just one set by pitch, from the lowest to highest notes. As they become more familiar with the bells, children will commonly learn how to play and compose little melodies.

The Silence Game helps the children develop a much higher level of self-discipline, along with a greater awareness of the sounds around us that most people take for granted. In this group activity, the teacher will get the children’s attention either by ringing a small bell or by hanging up a sign with the command "Silence". The children stop where they are or gather on the line, close their eyes and try to remain perfectly still.

The children sit still with their eyes shut and wait to hear the teacher whisper their name. When they hear it softly spoken, they silently rise and join together.

Sometimes the teachers will vary the Silence Game by challenging the children to carry bells across the room without allowing them to ring or they may use the calm atmosphere to introduce the children to guided visualization. At first younger children may not be able to hold the silence for more than 20 or 30 seconds, but gradually their ability to relax, listen and appreciate the perfectly calm environment increases. In many classes the Silence Game is an important daily ritual.

The Geometrical Cabinet is essentially a set of puzzles made in the shapes of the essential plane geometric figures. It consists of six drawers, each of which is fitted with several wooden frames inset with a geometric form. In addition to the familiar circle, square and rectangle, the child is introduced to a much broader array of complex figures, from the right scalene triangle to the decagon; and from the ellipse to the curvilinear triangle through the quatrefoil.

In addition to removing the puzzle pieces and replacing them in their frames as a puzzle, the children learn how to match them against three sets of printed cards that represent the same figures in increasing degrees of abstraction. The first set represents each shape completely colored in on the card in the same size as the piece from the cabinet. The children simply cover each card with the matching puzzle piece.

In the second set, the geometric shapes are printed as outlines drawn with broad lines that leave the inner area white. In the third set, the figures are simply traced with thin lines. As the children gradually begin to recognize the more abstract representations of the three-dimensional objects, they are preparing themselves to recognize the little lines and squiggles of the written word.

Gradually, children learn the names of each of the geometric shapes. Once the children begin to read and can verbally identify the shapes, they will begin to label them with pre-printed name cards. Eventually the children will be able to prepare their own cards from scratch.

The Geometric Solids - the logical extension of the Geometrical Cabinet is the set of Geometric Solids. The children learn the names of these wooden forms, identifying them first by sight and eventually when blindfolded. The set includes a sphere, cube, rectangular prism, a pyramid, triangular prism, ovoid, ellipsoid and a cone. The children quickly begin to look for each geometric form in their environment. They also begin to discover the relationship between the two-dimensional figures and the solid forms: a circle is related to a sphere, a square to a cube etc.

As they begin to read, children will learn to match geometric solids to a set of prepared label cards. Eventually, they will be able to prepare their own from scratch. This early introduction to Geometry continues in the Elementary Montessori program. After years of hands-on experience with geometric figures, children normally find it very easy to grasp more advanced concepts, from the definitions of geometric terms to the calculation of area, volume and circumference.

The Constructive Triangles allow the children to explore the geometric possibilities inherent within several types of triangles. The material consists of six boxes, each of which contains a set of brightly colored flat wooden triangles, which can be manipulated like a puzzle to form new geometric shapes. For example, two right triangles inverted and joined together along the hypotenuse form a rectangle. To help the young child recognize the essential relationships, most of the triangles have line drawn along those edges that join together with other triangles with a side of the same length to form new figures such as rectangles, squares, trapezoids and polygons.

The Constructive Triangles allow the children to explore the geometric possibilities inherent within several types of triangles. The material consists of six boxes, each of which contains a set of brightly colored flat wooden triangles, which can be manipulated like a puzzle to form new geometric shapes. For example, two right triangles inverted and joined together along the hypotenuse form a rectangle. To help the young child recognize the essential relationships, most of the triangles have line drawn along those edges that join together with other triangles with a side of the same length to form new figures such as rectangles, squares, trapezoids and polygons.

The Binomial and Trinomial Cubes are the most fascinating materials in the Montessori curriculum. At one level they are simply a complex puzzle in which the child is challenged to rebuild the cubes and rectangular prisms contained in the box back into the form of a larger cube. Color coding on the outside of the box and the sides of certain pieces helps the child detects the pattern.

The material is also an exercise in algebra and geometry, representing in concrete form the cubes of a binomial and a trinomial where a = 2 cm, b = 3 cm and c = 4 cm.

The Montessori Approach To Reading, Composition And Literature

The process of learning how to read should be as painless and simple as learning how to speak. Montessori begins by placing the youngest students in classes where the older students are already reading. All children want to "do what the big children can do", and the intriguing works that absorbs the older students involves reading; there is a natural lure for the young child.

Montessori teaches basic skills phonetically, encouraging children to compose their own stories using the Movable Alphabet. Reading skills normally develop so smoothly in Montessori classrooms that students tend to exhibit a sudden "explosion into reading", which leaved the children and their families beaming with pride.

The Sandpaper Letters are a set of prepared wooden tablets in which each letter is printed in white sandpaper, glued down against a smooth colored background. Dr. Montessori's research confirmed what observant parents have always known: children learn best by touch and manipulation, not by repeating what they are told. Her manipulative approach to teaching children to read phonetically is nothing short of simple brilliance and should have long ago become a basic element is every Early Childhood classroom around the world. Beginning at age two or three, Montessori children are introduced to a few letters at a time until they have mastered the entire alphabet. They trace each letter as it would be written, using two fingers of their dominant hand. As they trace the letter’s shape, they receive three distinct impressions: they see the shape of the letter, they feel its shape and how it is written and they hear the teacher pronounce its sound. The teacher and child will begin to think up words that begin with this sound: kuh (=c) - cat, candle, can and cap. Seeing the tablets for the letters c, a, and t laid out before them, the children will pronounce each in turn: kuh, aah, tuh: cat! To help children distinguish between them, consonants are reprinted against pink background and vowels against blue.

Many parents find it curious, that Montessori children are not taught the names of letters; instead they learn the sound that we pronounce as we phonetically sound out words, one letter at a time. For a long time, children may not know the names of letters at all, but will call them by the sounds: buh, cuh, aah etc. This eliminates one of the most unnecessary and confusing steps in learning to read: the letter "A" stands for apple. The sound it makes is "aah".

Many Montessori classrooms use Sandpaper Letters that do not follow the traditional circle and line approach of teaching a young child to teach. Both cursive alphabets and D-Nelian letters (a modified form of italic printing that facilitates the jump to cursive) are available and used with excellent results. Another unusual result of the Montessori approach is that young children will often be able to write (encoding language by spelling phonetic words out one sound at a time), weeks or months before they will be able to comfortably read (decoding printed words).

The Movable Alphabet - once the children have begun to recognize several letters and their sounds with the Sandpaper letters, they are introduced to the Movable Alphabet, a large box with compartments containing plastic letters, organized much like an old-fashioned printer's box of metal type. The children compose words by selecting a small object or picture and laying out the word one letter at a time. As with the Sandpaper Letters, they sound out words one letter at a time, selecting the letters that make that sound. The phonetic approach, which has mysteriously fallen out in many schools has long been recognized by educators as the single most effective way to teach children how to read and write. However, we have to remember that, unlike Italian and Spanish, English is not a completely phonetic language. Just consider the several different sounds made by the letters "ough". There is the sound "off" as in "cough", or "uff" as in "rough" or "enough", or the sound "oooh" as in the word "though", or the sound "ott" as in "thought". Altogether, there are 96 different phonograms (combinations of letters that form distinct sounds) in the English language. (such as ph-, -ee, ai, oo, etc.).

It is not surprising that in the early years, as young children are beginning to compose words, phrases, sentences and stories their spelling can sometimes get a bit creative. For example, the word "phone" is frequently spelled "fon". Montessori teachers deliberately avoid correcting children's spelling during these early years, preferring to encourage them to become more confident in their ability to sound word out rather than risk that they will shut down from frequent correction.

The process of composing words with the Movable Alphabet continues for many years, gradually moving from three-letter words to four- and five-letter words with consonant blends (fl, tr, st etc.) double vowels (oo, ee etc.) silent e's and so on.

The Metal Insets - First Steps to Writing. Dr. Montessori found, that children in her schools were capable of encoding words months before they developed the eye-hand coordination needed to control a pencil. By using specially prepared movable alphabets, Montessori separated the process of beginning to write from its dependency on the child's ability to write with paper and pencil. To help children develop the eye-hand coordination needed to grasp and write correctly with a pencil; Dr. Montessori introduced them to a set of metal frames and insets made in the form of geometric shapes. When the geometric inset is removed, the children trace the figure left within the frame onto a sheet of paper. Then they use colored pencils to shade in the outline they have traced, using careful horizontal strokes. Gradually children become more skilled at keeping the strokes even and staying within the lines. As they get older, children begin to superimpose several insets over each other, creating complex designs which, when colored in, resemble stained glass. Montessori children will often prepare beautiful little books of their Metal Inset work.

Early Reading Exercises - As children learn to work with the Sandpaper Letters, the teachers will lead them through a wide range of pre-reading exercises designed to help them recognize the beginning and later the ending and middle sounds in short phonetic words. One common example would be a basket containing three Sandpaper Letters, such as c, b and f. In addition, the basket will contain small dime-store objects that are models of things being these letters. The basket described above might contain little objects representing a cat, cat, bug, bag, bat, flag, frog, and fan. Other exercises will substitute little cards with pictures instead of the small objects.

Cards with the names of familiar objects are commonly found in most kindergartens. However in Montessori, children take this a bit further, learning the names of and placing the appropriate labels on a bewildering array of geometric shapes, leaf forms, the parts of flowers, countries of the world, land and water forms and much, much more.

Montessori children are known for their incredible vocabularies. Where else would you find four year olds who can identify an isosceles triangle, rectangular prism, the stamen of a flower or Asia?

When Will Children start to read?

There is typically a quick jump from reading and writing single words to sentences and stories. For some children, this "explosion into reading" will happen when they are four; for others when they are five and some will start to read at six. A few will read even earlier, and some others will take even longer. Most will be reading very comfortably when they enter first grade, but children are different and as with every other developmental milestone, it is useless to fret. Again, the children are surrounded by older children who can read and the most intriguing things to do in the classroom depend on one’s ability to read. This creates a natural interest and desire to catch up to the big friends and join the ranks of readers. As soon as children, no matter how young they are, show the slightest interest, we begin to teach them how to read. And when they are ready, the children pull it all together and are able to read and write on their own.

Command Cards are used with older children to suggest specific challenges in every area of the curriculum. For example, in Geography, a command card might challenge the child to look in the atlas and find the location of the largest inland lake on the Earth.

Teaching Children the Consonant Blends and Phonograms of the English Language - Montessori uses two sets of small Movable Alphabets, each made off a different color, to help the children master consonant blends, such as fl, st, ch, cl, cr, or tr. A consonant blend requires the child to blend two distinct letter sounds together into one, as we do when we say "flag" or "train". The child lays out several copies of the consonant blend with one color of the Movable Alphabet. Then the child completes the small words by adding the remaining letters in the Movable Alphabet printed in the second color. An example might be tr..ip, tr..ade, tr..ain etc.

Phonograms are combinations of vowels in the English Language that form new sounds on their own, such as ee, ai, oa, and ou. Some phonograms, such as "ough", can make more than one sound. For example, ough has one sound in "cough", another in "although" and still another in "through". The children construct words containing phonograms using two Movable Alphabets just as they do with the consonant blends.

Montessori teachers will normally prepare little booklets, each of which contains many examples of one particular consonant blend or phonogram.

Puzzle Words - some words, most of which have come to English from other languages, just don't follow the familiar rules. Examples of Puzzle words are: the, was, you, they and their. They have to be learned by memory.